Immunotherapy Treatment for Alzheimer’s Disease

By Annette Pinder

Alzheimer’s is one of the most common and most heartbreaking diseases, robbing individuals of their memories, self-sufficiency, and even their personalities. Nearly 7 million Americans over age 65 live with Alzheimer’s, a number projected nearly double by 2050.

Jonathan Lovell, PhD, a professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering at the University at Buffalo, is developing a novel immunotherapy to treat Alzheimer’s, and leads a research team working on a vaccine that targets multiple sites within the key polypeptides of amyloid-beta (Aβ) and tau, which are hallmarks of the disease. The immunotherapy concept published in the August issue of the journal Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, suggests that the body can mount an immune response to multiple epitopes in response to these polypeptides, which are parts of those proteins that the immune system can recognize.

“What distinguishes our approach is that we’re not just targeting one epitope in Alzheimer’s, we’re targeting multiple ones,” Lovell says, explaining that he hopes to train the immune system to recognize and attack these problematic proteins. Lovell has been working with researchers at the Institute for Basic Research in Developmental Disabilities (IBR), based in Staten Island, NY, to show that the immunotherapy can prevent and reduce Alzheimer’s-like changes in mice that have been genetically modified to develop a condition similar to Alzheimer’s. The team also collaborated with the Buffalo startup POP Biotechnologies, co-founded by Lovell and universities and hospitals in Canada, Japan, and Korea.

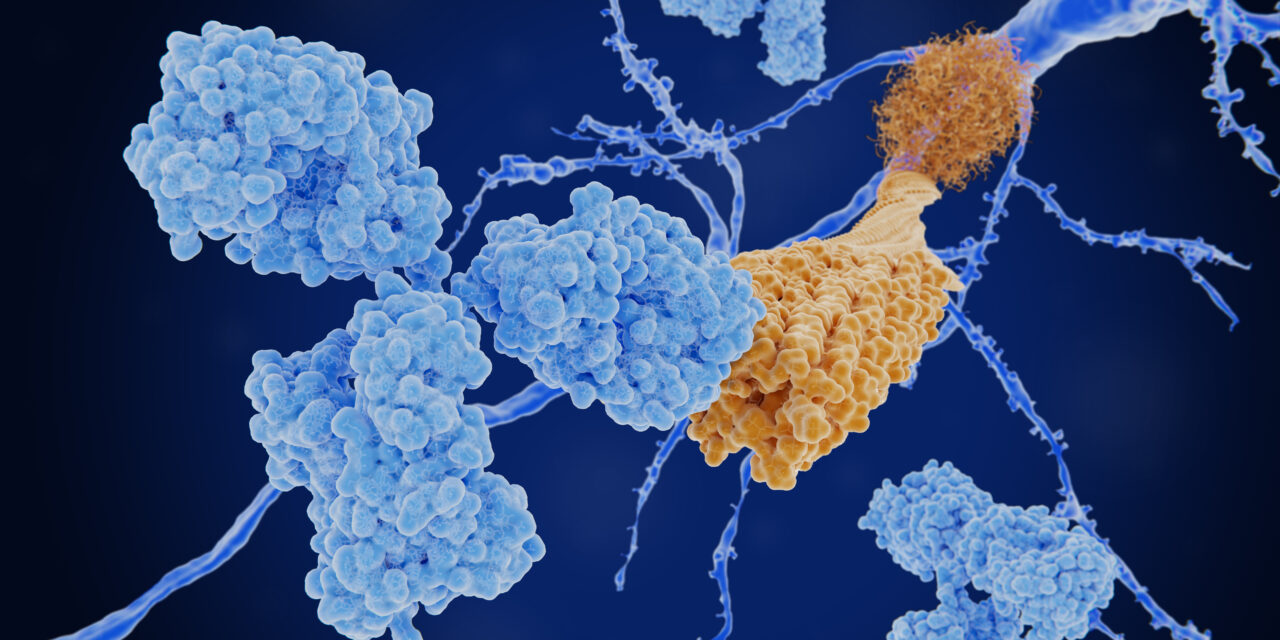

Alzheimer’s has two main disease hallmarks: Amyloid plaques, made of mainly amyloid beta (Aβ), that build up outside brain cells, and neurofibrillary tangles of the protein tau inside the brain cells. Together, they affect memory, the ability to find words, work with numbers, make decisions, and follow familiar routes and directions. Lovell’s idea is to have the antibodies clear these plaques and tangles, to reverse or slow their progression.

The immunotherapy Lovell and his team developed uses the key polypeptides mixed with special liposomes to deliver the vaccine and boost the immune response.

Hoping to begin human trials here in the US and overseas within the next few years, Lovell says, “What we’ve found is that the mice that received the immunotherapy early on showed fewer signs of Alzheimer’s-related brain damage and performed better in cognitive tests. The vaccine appears safe and didn’t cause unwanted side effects.” While the researchers originally administered the vaccine early on, before the mice developed significant symptoms of dementia, they are now testing it on older mice with the disease to see how they fare.

“The underlying technology of this immunotherapy has already been tested in humans in Korea for a COVID-19 vaccine, and we would support working with partners there to advance the translation of the technology there,” Lovell says. He notes the first step is to establish manufacturing standards, and then improve important metrics such as safety testing prior to human testing. “Alzheimer’s is such a devastating disease that we need bold solutions to address it,” Lovell says.