Confused About the Measles Vaccine?

According to a recent New York Times article, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has reported more cases of measles in 2025 than in any previous year. With about 95% of the population vaccinated, measles was considered eradicated in the U.S. by 2000. However, with 1,288 confirmed cases and vaccination rates at around 93% or less in some regions, our ability to maintain this status is threatened. Even more alarming is that the World Health Organization (WHO) reported over 9 million measles cases and approximately 136,000 measles deaths worldwide in 2022.

The CDC reports that most measles cases in the United States are linked to an outbreak in Southwest Texas, which then spread to New Mexico and Oklahoma. Cases have now been reported in 38 states, including Montana, Colorado, New Mexico, North Dakota, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, Iowa, Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Tennessee, Ohio, Kentucky, and Pennsylvania.

“Measles is one of the most contagious diseases known to humans,” says the CDC. The virus spreads through respiratory droplets when an infected person coughs or sneezes and can stay in the air and on surfaces for hours, making crowded and enclosed spaces especially risky. The basic reproduction number (R0) for measles is estimated to be between 12 and 18, meaning that each infected person can pass the virus to 12 to 18 others in a susceptible population. This high transmissibility explains the rapid spread during outbreaks, especially in unvaccinated populations and in crowded venues.

According to the CDC, the initial symptoms of the measles virus resemble those of many respiratory infections and include high fever, cough, runny nose, and red, watery eyes. A few days after symptoms start, a distinctive red rash appears, usually starting on the face and spreading across the body. Other classic signs include Koplik spots—tiny white spots inside the mouth, which are considered a hallmark of measles. While many recover from measles without long-term effects, the disease can lead to severe and sometimes fatal complications, especially in young children, pregnant individuals, and those who are immunocompromised. Common complications include otitis media (ear infections), pneumonia (which causes many deaths), diarrhea (leading to dehydration), encephalitis (brain swelling that can cause permanent damage), blindness, and subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE). SSPE is a rare but deadly neurological disorder that can develop years after infection. Of particular concern is that measles can also cause “immune amnesia,” in which the immune system forgets previous pathogens, leaving individuals more vulnerable to other infections for months or even years after recovering from measles.

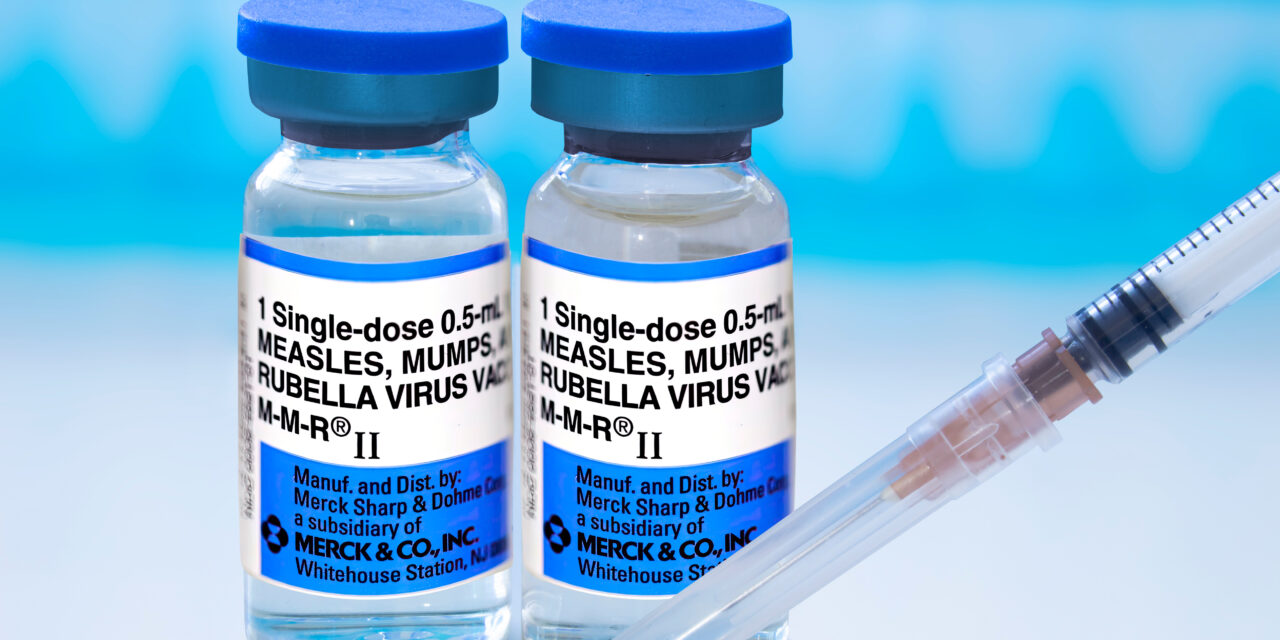

The American Pediatric Association says that the measles-mumps-rubella (MMR) vaccine is crucial for preventing measles and highly effective, with two doses offering about 97% protection against the virus. Achieving herd immunity and preventing outbreaks requires high vaccination coverage, usually over 95%. Every parent and caretaker should be concerned that, for every 1,000 children who contract measles, one or two will die. So far this year, two unvaccinated children and one adult have died from the virus, the highest number in over ten years.