The Science of “Mindfulness”

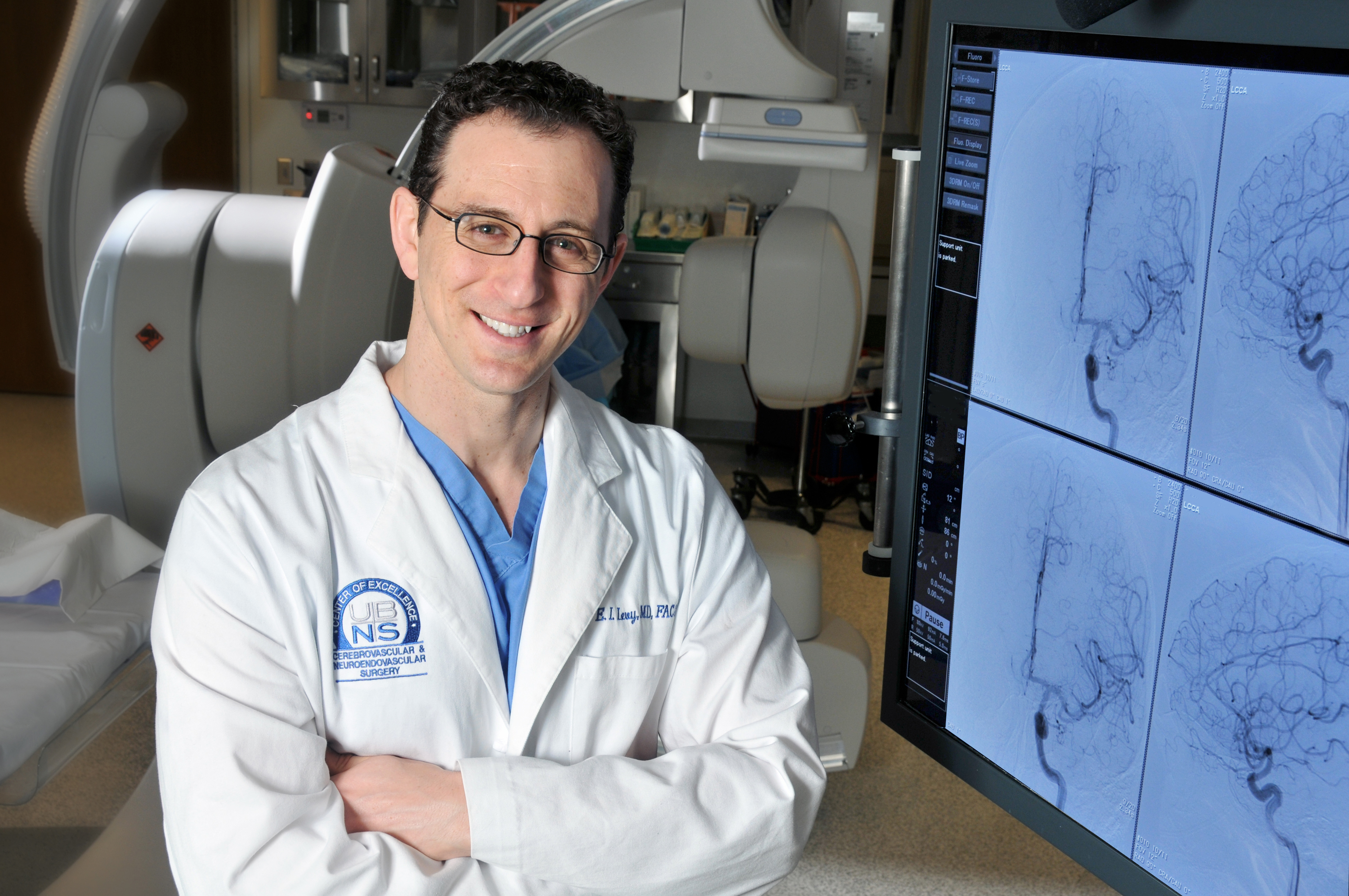

by Elad I. Levy, M.D., M.B.A., Professor and Chair of Neurosurgery, SUNY at Buffalo

and Scott E. Friedman, J.D., LL.M., Chair, Lippes Mathias Wexler Friedman LLP

Background

In this era of tweets, texts, snaps, emails, and instagrams, our brains are bombarded by….”sorry I had to check my Facebook”….”where was I?” Oh yes, our brains are bombarded by sensory overload. The ongoing technological advances of the 21st Century develop at a pace that is impossible for anyone to keep up with and our already overloaded senses are rendered numb by random and chaotic bits of digital information that are typically unrelated to the moment we are living in.

In this ever-evolving world of social media, our minds become addicted to superficially scanning often trivial and unimportant pictures, vignettes, and countless other content from an ever expanding base of “friends” (who are often people we barely know!) over a variety of digital platforms. And if we don’t process the message in 5 seconds, we sometimes don’t even get a second chance (Snapchat content disappears after a short glance). How often are we introduced to people and immediately ask ourselves “what was her name again”? How could we have been that disinterested or unfocused that we forgot a name immediately after an introduction? How often do we glance at our phones during a conversation because we wonder if there is something more important on our phone than the person standing in front of us?

Our distinctly human minds are hardwired to allow us to reflect on the past as well as anticipate the future. Without discipline, however, this extraordinary attribute can cause us to randomly jump from thought to thought… to thought…diminishing our attention span to, say, that of a common flea. Few of us have the mental fortitude to focus on one topic without letting our minds wander. And modern technology has made this inherently human problem even worse. A lot worse.

An Introduction to “Mindfulness”

The ability to remain mentally focused is commonly referred to as “mindfulness.” Mindfulness has been the subject of practice by many religions, including, perhaps most notably, Zen Buddhism for over two thousand years. In recent years, neuroscientists have been studying the impact of mindfulness practices and have demonstrated, with scientifically validated data, that the practice provides multiple important benefits, including:

- Reducing stress and anxiety (and, consequently, depression) by reducing the time spent ruminating on past or anticipating future events instead of focusing on the “present;”

- Significantly boosting working memory capacity;

- Improving one’s ability to accomplish a task by sustaining focused attention (and suppressing distracting information);

- Reducing emotional reactivity;

- Enhancing cognitive flexibility and increasing information processing speed; and

- Improving relationship satisfaction by enhancing empathy and compassion.

Mindfulness has also been demonstrated to provide numerous health benefits, including increased immune functioning while reducing fatigue, anger and stress-related cortisol compared to control groups. Ongoing research suggests that meditation may help people manage symptoms of conditions such as anxiety disorders, asthma, high blood pressure, pain, and sleep problems. In short, “mindfulness” can enhance one’s quality of life in multiple ways.

Mindfulness as a Discipline

Like weight training for muscles, mindfulness requires discipline and practice. Some of the more common techniques to practice mindfulness include:

- Mantra meditation, in which one sits silently, while repeating a calming word, thought or phrase to prevent distracting thoughts;

- Mindfulness meditation, in which one focuses on observing a particular sensation, such as the in and out flow of your breath; and

- Yoga, in which one performs a series of postures and controlled breathing exercises to promote (in addition to a more flexible body) concentration on the moment.

One of the authors of this article often achieves mindfulness through brain surgery. As the surgery becomes more intricate, and as the surgical team approaches the critical portions of the surgery, I ask that the lights be shut off so all we see is the light of the high-powered microscope focused on millimeters of brain tissue and brain vessels. I ask all cell phones to be muted and all non-urgent conversation to cease. At this point, the din of the hum of the electric ventilator can be heard as a white noise. I can hear my breath, and I can feel my heart beat slowly as I consciously try to calm myself. The surgery becomes mechanistic, and I am at peace in a deep concentration where time no longer exists. Our focus has shifted from a potentially life threatening disease state requiring delicate and sometimes risky surgical maneuvers, to a peaceful symphony of coordinated balanced movements bringing us closer to a well thought out objective. And should intra-operative bleeding or concerning issues arise, the surgeon who remains especially calm sets the tone for the surgical team, increasing the likelihood of an optimal outcome.

When experiencing mindfulness, five minutes or fifty minutes feel no different. When the critical portion is finished, the microscope is removed, overhead lights come on, and the chatter of the other members of the surgical team resumes. At this point I see a clock and I am transformed back to a place of business. As we gain more comfort and experience in these settings, it is possible to achieve these moments of mindfulness, where I personally believe we can perform our tasks at our highest potential.

We have both found similar transformations when achieving a personal best in athletics, whether on the squash courts, on a rowing machine, a run, or a spin bike. Or swimming for many laps for distance and simply focusing on one or two aspects of the technique. We both spent years rowing, Scott in high school and Elad in college. We’d spend many hours on ergometers and in boats, developing muscle memory for an automated rowing motion. These workouts were painful, tedious, monotonous, and any other negative adjective one can think of. But when we were faced with erg testing (a challenge to push one’s body to the limit), we would achieve personal bests when we found mindfulness- the ability to focus on perfection of form at a specific pace – but not on the lactic acid that would build up and cause pain, muscle fatigue, and burning lungs. Achieving these states of focus required mental preparation the night before and morning of these challenges, and when accomplished, a state of inner bliss (often confused with exhaustion) often lingered throughout the day. Perhaps this is one reason why exercise can rejuvenate our mind?

In short, achieving mindfulness – at home, at work or at play – can provide immense satisfaction while providing a variety of positive benefits. What has become increasingly clear is that now more than ever, we must find opportunities to retrain our minds how to focus – and to ignore the tweet, the text, or the snap of the moment. We encourage you to find a “quiet mind,” whether through a practice of meditation, yoga, sports or otherwise. It may be one of the most important actions you can take for yourself and those who fill your day.

Namaste