By Bert Gambini

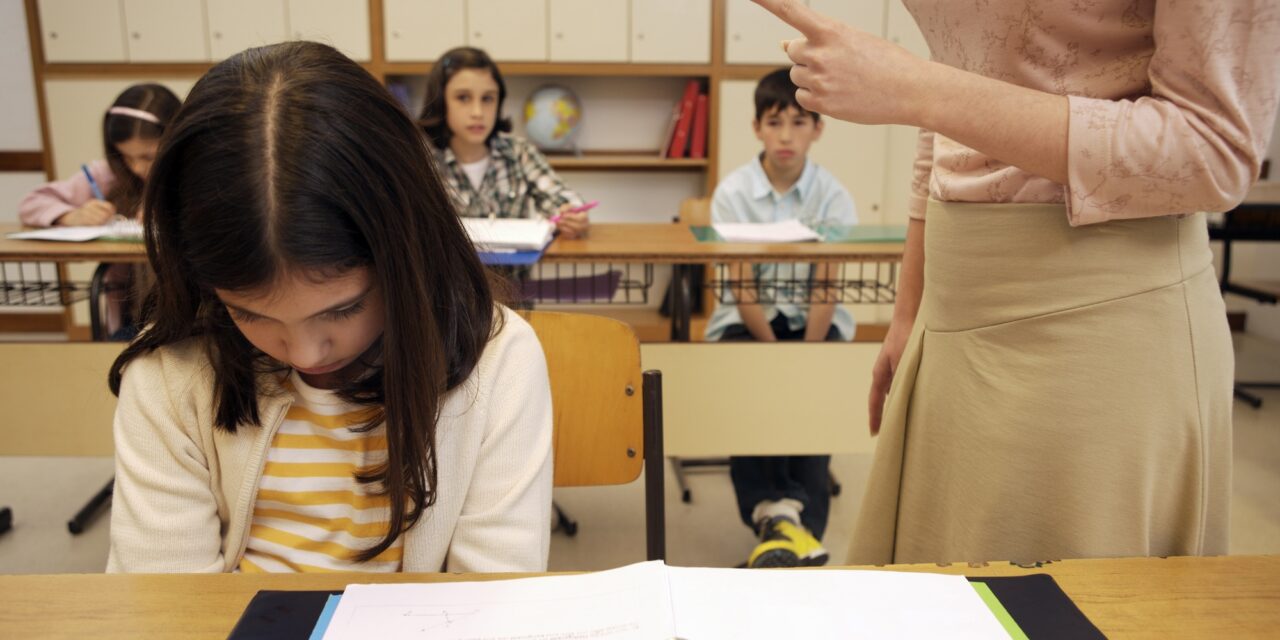

Research on school discipline has focused largely on the effects of exclusionary measures across the life course. However, a University at Buffalo sociologist has published a new study suggesting that a fuller range of disciplinary experiences, not just the most severe punishments, has detrimental health and well-being implications for students later in life.

The findings published in the journal I identified three distinct histories of discipline among college-educated emerging adults, a group unlikely to receive the most exclusionary types of discipline. This broader conceptualization of discipline, based on a unique sample of young people, demonstrates the need to think more expansively about the consequences of disciplinary practices.

Suspension and expulsion are closely related to the school-to-prison pipeline, but this study suggests that discipline’s effects also apply to those who make it to college, not in the form of criminal justice involvement, but in terms of poorer health. Avoiding negative outcomes associated with punishments, while creating an environment conducive to learning, requires understanding the effects of discipline beyond punitive methods, according to Ashley Barr, PhD, UB associate professor of sociology, and the study’s corresponding author.

“The current generation of young adults came of age as schools began pulling back on zero-tolerance policies, but racial, class, gender, and ability disparities remain,” says Barr. “It’s time to rethink school discipline entirely. Narrow conceptions of exclusionary discipline, limited to expulsion and suspension, don’t capture most of the disciplinary practices experienced by students.”

Barr and co-author, Zhe Zhang, a doctoral candidate in UB’s sociology department, used survey data from over 700 college-educated young adults categorized into three groups: Those who were minimally disciplined; those who experienced school-managed discipline, like loss of privileges, written reprimands, or in-school detention; and those who received intense discipline likely to involve parents, counselors, or law enforcement. Participants with a history of school-managed discipline reported more depressive symptoms and worse self-rated physical health than classmates who were minimally disciplined. Young adults who experienced intensive discipline reported worse self-rated physical health than those in either of the other groups.

“Our analysis shows that the disciplinary histories of this relatively privileged group of college educated participants did not break down into a simple dichotomy of exclusionary and non-exclusionary,” says Barr. “Although this finding could be due to the privileged nature of the sample, it is consistent with other research suggesting that most school discipline is not what we typically consider exclusionary and that discipline often begins with school-managed measures, and proceeds, often more quickly for students of color, to exclusionary measures.”

Asserting that these disparities demand attention, Barr says, “Even in this college educated sample, we see dramatic disparities in who received intensive discipline.” Thus, she encourages other studies along this same research line using a nationally representative sample, saying, “Assuming the findings are replicated, I think disciplinary practices need to stay on the radar in school policy discussions, beyond the rollback of zero-tolerance policies.”

Bert Gambini is the News Content Manager for University at Buffalo.