By Judith G. Fales

When everything is working well, the brain allows us to think and move well, and to express appropriate emotions. Our immune system protects us from getting sick and promotes healing when we are unwell or injured. But what happens when that system, usually our friend and protector, becomes the enemy as it does for anyone with multiple sclerosis (MS)?

MS is a brain disease caused by an overactive immune system, and is the most common neurologic crippler of young adults. Its symptoms include numbness, tingling, visual problems, lack of coordination, and bladder and bowel difficulties. MS affects nearly one million people in the U.S. and impacts 2-3 times more women than men.

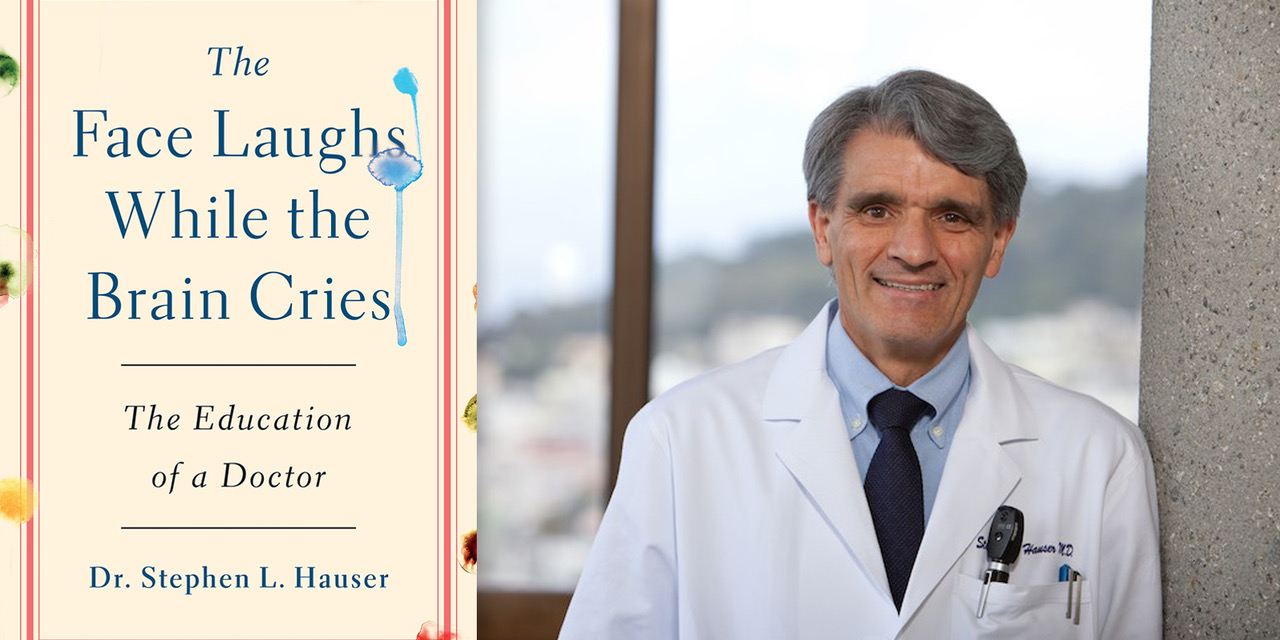

Dr. Stephen Hauser is a Distinguished Professor of Neurology at the University of California, San Francisco and director of the Weill Institute for Neurosciences. He is a physician and a scientist. Over a career spanning nearly a half century, Dr. Hauser ’s work led to the scientific breakthrough that paved the way for a revolutionary treatment for MS. His recent book, “The Face Laughs While the Brain Cries,” is both an autobiography and the amazing story of his desire to help people with MS.

Myelin is a protective insulating substance around nerve cells in the brain and spinal cord. Lymphocytes are types of white blood cells in the immune system, including T cells and B Cells, which normally help us fight off infections. But when someone develops MS, lymphocytes attack the nervous system, and especially myelin. For many years, it was believed that T cells were the sole culprits in MS. However, experiments with T cells didn’t produce the tissue changes that resembled those found in MS in humans, and drugs targeting T cells were not successful in treating MS.

Working with many colleagues, including Dr. Norman Letvin, a leader in HIV/AIDS research, Dr. Luca Massacesi and Dr. Claude Genain, Dr. Hauser developed a new laboratory model of MS. Experiments using that model led to the realization that it was B cells and not T cells which caused MS. Next, he showed that the B cell killing drug Rituximab, first developed for use in patients with B cell lymphoma, could be repurposed to successfully treat MS. This then led to the development of even more advantageous B cell targeting drugs for MS, first Ocrelizumab and then Ofatumumab. The news from these studies is wonderful. There is a near complete absence of new brain inflammation, progressive deterioration slows, and there are no serious safety concerns even after many years of use. For patients whose MS is beginning today, most can expect a life free from disability.

Dr. Hauser says that because of these discoveries, there are new generations of therapies under development that will hopefully be even more effective. He adds, “Not only can we look toward turning off the symptoms of MS permanently without the need for ongoing therapy, but there is also the possibility that a cure, and even prevention of the disease, will be possible.”